Unintended Consequences

The Destabilizing Effect of El Chapo's Capture on Mexico's Cartel Landscape

Recently, I listened to a talk by Peter Zeihan. Peter is a popular geopolitical commentator who lectures businesses and trade associations, along with his media appearances. Regardless of how you feel about his views, he commented on something I thought was interesting: After El Chapo’s capture, the Drug Cartels in Mexico fragmented, fighting one another, moving from a violent but stable system to a new internal order that proved to be violent and chaotic. The crux of this argument is that the capture of El Chapo removed a kingpin that was more focused on business, allowing for groups more focused on warfare to grow, such as Jalisco New Generation and Los Zetas.

These statements raise two critical questions: First, did El Chapo’s presence create a form of stability and rule of law, even if that law was unjust and harmful? Second, if some level of stability existed, did the removal of El Chapo destabilise the region, and who bears responsibility for this ensuing instability?

El Chapo, Sinaloa Cartel and Violent Stability?

In Zeihan’s presentation, he suggested that El Chapo ordered Sinaloan sicarios to follow a few basic rules, such as:

Don’t engage in petty crime

Don’t steal pensions

Don’t mug people

In essence, El Chapo simply wanted to focus on the core competencies of drug creation and smuggling, and other “ventures” had to be cleared with the leadership and ultimately supportive of the “business.”

I am sceptical of Zeihan’s claim that El Chapo and Sinaloa provided some kind of law and order. The Cartel seems to have provided stability, mainly in northern Mexico, where they are primarily based. For instance, reports from Culiacan on Ovcidio Guzman’s (El Chapo’s son) arrest and subsequent conflict suggested that locals were actually in support of the Sinaloa Cartel. Their support may stem from the group bringing money to the region and the perception that the cartel would still be there even if federal troops withdrew. Ultimately, the cartel 'ensured relative stability, if not peace' in the region. However, it's crucial to consider other factors contributing to this perception. Economic conditions, the role of local politics, and the historical context of cartel influence all shape this dynamic.

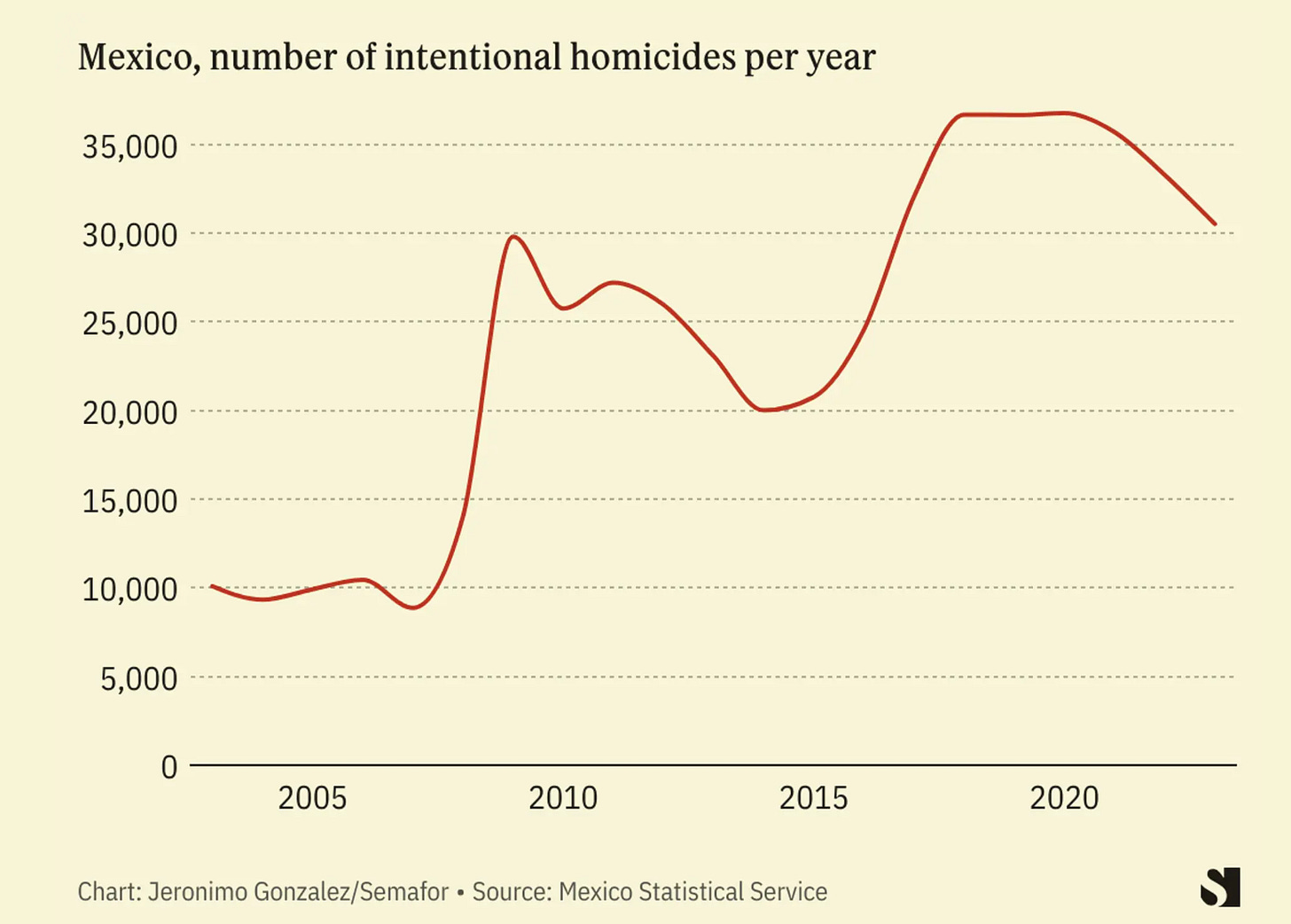

However, one thing that stands out is the violence accompanying the stability of Sinaloa’s rule. Following the Mexican government’s ‘declaration of war’ on organised crime in 2006, violence skyrocketed, from about nine deaths per 100k in 2007 to twenty-four in 2011. However, over the following decade, homicides declined as various Cartels consolidated their power in their regions. The murder rate then declined over four years from the peak down to 17 deaths per 100k per year.

How was Sinaloa able to provide stability while enacting high levels of violence? Vanda Felbab-Brown says:

“Being a decades-old and very successful criminal group, the Sinaloa Cartel’s self-presentation is one of buttoned-down criminals whose oppressive rule comes with predictability and some level of moderation. Indeed, a key hallmark of the Sinaloa Cartel has been a rather careful calibration of violence that imposes its domination in a form in which local politicians, businesses, and people can develop predictable coping mechanisms. In contrast to CJNG, the Sinaloa Cartel keeps a lower, behind-the-scenes profile, one of “polite extortionists who bring in order, who are civilised criminals, who don’t just drag in violence for the sake of violence,” as a businessman in Baja California Sur whom I interviewed phrased it.”

Further Felbab-Brown provided an insightful quote from fieldwork conducted in Tijuana:

“During the war [among the Sinaloa and Tijuana Cartels and their local proxies as well as smaller independent criminal groups], life was very difficult. You had to pay [extortion] to many groups. All the time, someone was showing up at your door and threatening to burn down your businesses and kill your family. The prices were going up and up, just about weekly. And if one group found out you had paid their rivals, they would also threaten you and your family, even though there was no way to resist. I was considering just selling all my restaurants. But now that Sinaloa won, things are good. You need to pay just once, not weekly, only monthly, and the fee has gone down; it’s all easy. They are polite. And they keep the health inspectors and government tax people who used to harass us and ask for hefty bribes away from our necks.”

There seems to be a sense of peace and predictability once one of the cartel groups, principally the Sinaloa, has won a war over another and solidified its territory. Some of this, though, is helped by the corruption and inability of Mexican governing officials to provide safety for the general population if Mexican officials seek bribes and regulate local businesses. At the same time, cartels take smaller cuts from people’s incomes and businesses' revenues and don’t impose restrictions that the state might; locals will, of course, see them as more legitimate.

The key issue, however, is that Mexican officials and the United States, in removing the leader of the largest cartel, may have disrupted this stability.

Regional Destabilisation

In 2016, Mexican authorities captured El Chapo and extradited him to the United States the following year. This capture was a result of extensive collaboration between Mexican forces and U.S. agencies like the DEA and FBI, which provided critical intelligence. Following his capture, the Sinaloa Cartel experienced significant internal turmoil. Key lieutenants vied for power, leading to infighting and the fragmentation of the cartel. This internal strife weakened the cartel’s ability to maintain control over its territories, creating opportunities for rival groups to expand.

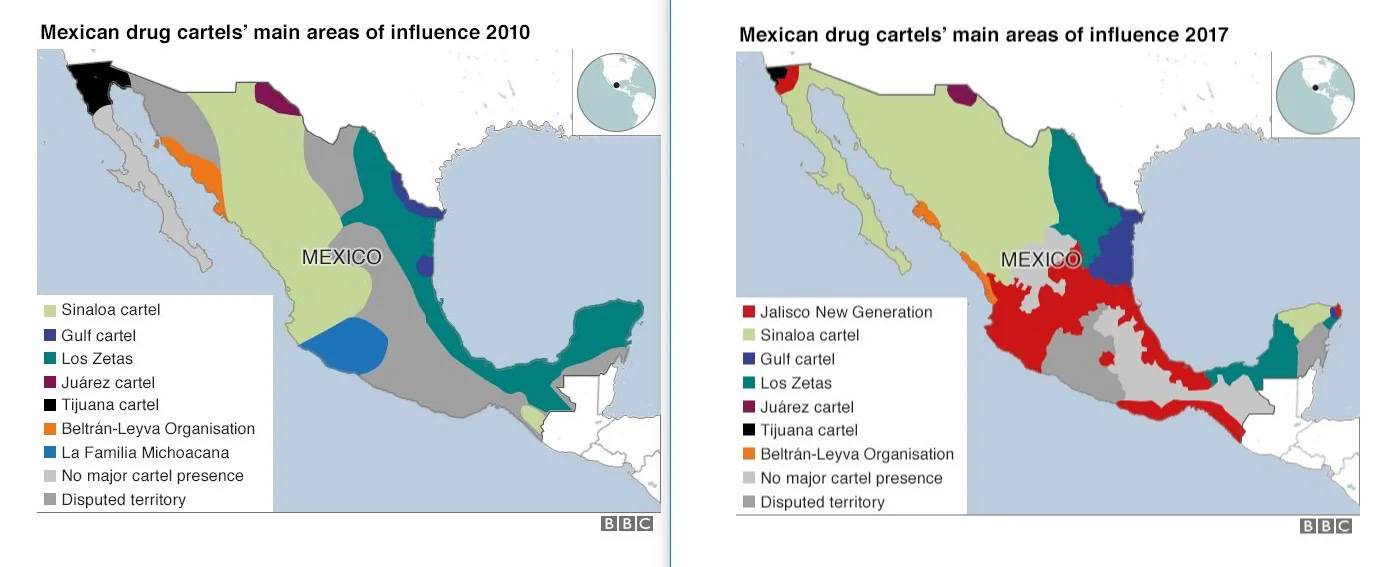

However, El Chapo’s capture set in motion a chain of events that has seemingly caused greater chaos. Since the capture, the Sinaloa Cartel has splintered, strengthening regional groupings and empowering new factions. High and mid-level commanders vied for control, creating new power structures and control over their autonomous territories. Ultimately, the in-fighting has weakened the Sinaloa Cartel’s control over its territories and allowed other cartels the opportunity to grab power.

The main group that has benefitted from the weakening of the Sinaloa Cartel is a group that some have labelled a splinter from Sinaloa: Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). CJNG, founded around 2010, has rapidly become one of Mexico's most powerful and violent criminal organisations. Led by Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, aka "El Mencho," the CJNG is notorious for its extreme brutality and sophisticated operations. They have expanded their reach globally, engaging in drug trafficking, money laundering, extortion, and arms trafficking. The cartel's strategic use of alliances and violent rivalries has allowed them to dominate key territories in Mexico, challenging the long-standing power of the Sinaloa Cartel and other criminal groups such as Los Zetas, another particularly violent group.

The CJNG's influence extends beyond Mexico, impacting international drug markets and contributing to significant violence and instability within Mexico, especially as they seem to eschew the business-like mindset of the Sinaloa Cartel and are more focused on warfare as a way to expand their operation. Their aggressive tactics and organised structure pose severe challenges to law enforcement, both locally and internationally. The cartel's activities have strained US-Mexico relations and highlighted the complexities of combating transnational organised crime. Despite efforts to curb their influence, the CJNG remains a formidable and resilient force in the criminal underworld.

Ultimately, the splintering of the Sinaloa Cartel has shifted the order in Mexico from a few dominant cartels to numerous, smaller and more localised groups seeking to control their piece of the drug trade into the United States. This fractured order has inevitably led to an increase in violence as groups constantly battle with one another for control.

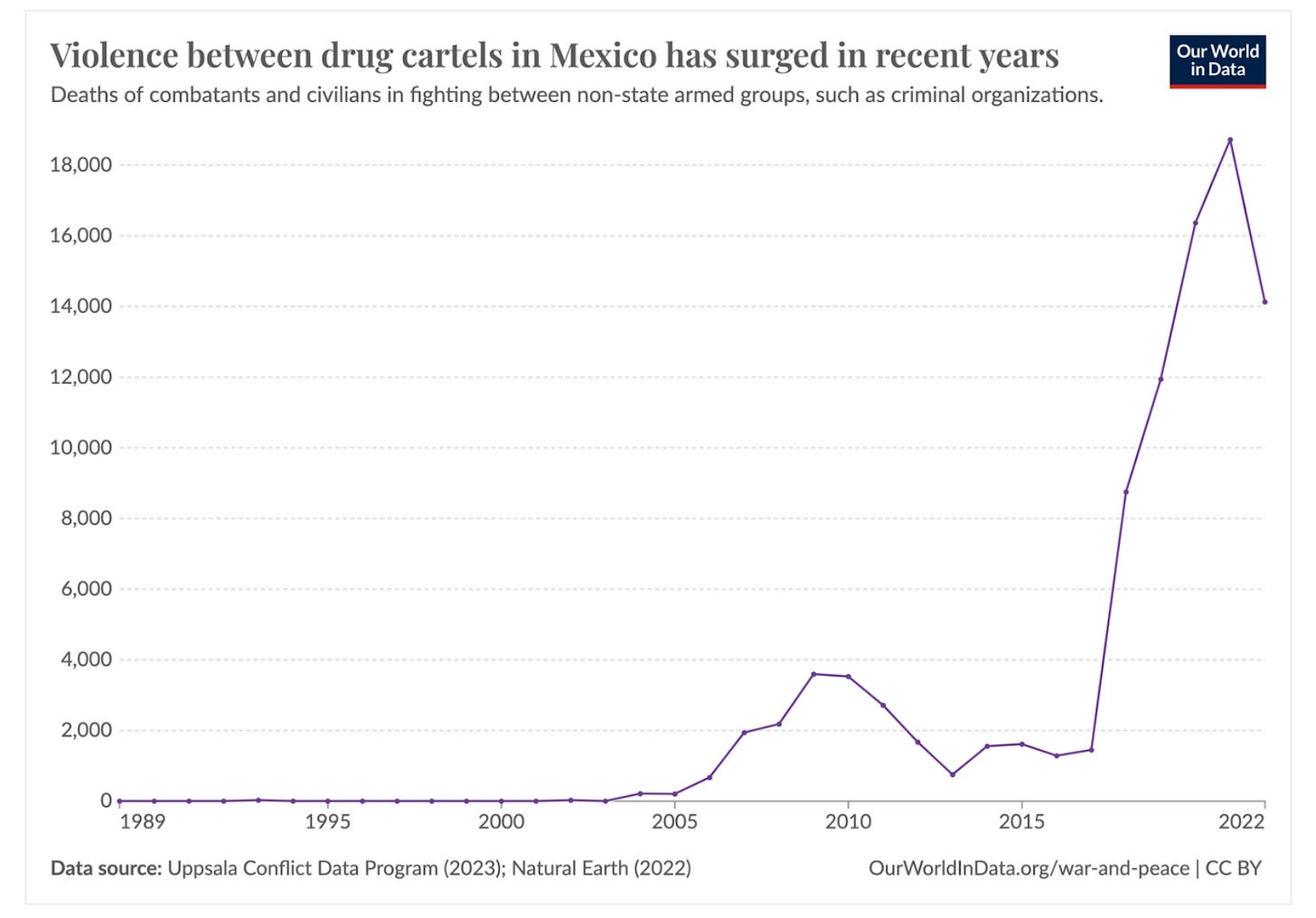

The splintering of Sinaloa and the proliferation of other violent cartel groups has increased violence throughout Mexico. Overall, the murder rate has shot up, from just over 17 per 100k in 2015 to 26 in 2017, nearly 30 in 2018 and levelling at roughly 29 since 2019. Further, as the graph above shows, the removal of El Chapo, the splintering of Sinaloa and the proliferation of other cartel groups led to a significant increase in cartel v. cartel violence - a roughly 7x increase in violence between Cartel groups.

Ultimately, it seems that the removal of the head of the largest Cartel destabilised much of Mexico. The Sinaloa, the largest and most powerful cartel, splintered and allowed other cartel groups to operate, leading to greater levels of violence and destroying even the little stability that reigned under Sinaloa rule.

Who Destabilised the Region?

Ultimately, Zeihan’s proclamation that the United States destabilised the region may be partially true. For the US part, authorities have targeted Cartels, especially Sinaloa, through various mechanisms. The US targets cartels through sanctions, such as those recently levied on the La Nueva Familia Michoacana Cartel, aiming to reduce their ability to fund their operations and work with international partners. US authorities also leverage their extensive intelligence capabilities to support Mexican authorities, who execute raids searches and generally work on the ground. Further, the US evokes extradition policies aimed at compelling Mexican authorities to send key wanted Cartel leaders to the US for trial, sentencing and, ultimately, prison in the United States.

Mexico, on the other hand, has had a more direct role in the fight against the cartels. In 2006, the government launched their war on drugs, which saw efforts by both law enforcement and the military to engage with cartel groups. Law enforcement, under pressure from the US, has pursued a goal of taking out the key kingpins of the cartels in a sort of “Cut the head off the snake and the body withers” strategy. Further,m military involvement has exacerbated the violence through heavy-handed tactics and military-grade equipment being involved in street warfare. On top of this, corruption within law enforcement and leading officials has created an atmosphere where some people will actively side with cartel groups, as the quote above illustrates. Further, Mexican governing institutions are generally weak and struggle to cope with fighting back against challenges to the state’s authority.

Ultimately, it seems like a team effort has allowed for regional destabilisation. The United States, to combat the drug epidemic and, more recently, the migrant crisis, has put pressure on Mexico to root out and take out the leaders of the cartels, helping through intelligence efforts and other support that doesn’t require boots on the ground. Mexico has utilised law enforcement and military units to combat the cartels, successfully capturing some leading cartel bosses but increasing violence and instability in the process.

But if both the United States and Mexico have contributed to the destabilisation, how can they effectively combat the cartels? What strategies might be successful? Some experts have suggested treating the cartels as a threat similar to terrorist organisations, potentially involving U.S. military intervention. However, this approach raises significant questions about feasibility and effectiveness. Historical examples, such as Colombia's battle against the Medellín and Cali cartels, show that a combination of targeted enforcement, socio-economic reforms, and international cooperation can yield results. In the next article in this series, these questions will be explored in greater depth, examining potential strategies and their implications for both nations.