Picture: Jer Clarke/ (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) licence

Electoral reform is once again in the headlines in the UK. Following the Labour Party's unsurprising victory in the 2024 General Election, commentators noticed major disparities between the popular vote and seat allocation in Parliament. However, this isn’t the first time the UK has seen major disparities between the popular vote and the number of MPs in Parliament. This pattern of disproportionate representation has been a recurring issue, raising questions about the legitimacy and fairness of the electoral process over several decades.

But why is this? What makes the UK electoral system prone to these disparities? And is there any movement to change this voting system? Despite the system's simplicity and historical use, its tendency to produce disproportionate results has led to growing calls for electoral reform. The UK's First Past the Post (FPTP) system is increasingly being questioned for its ability to represent the electorate's will fairly.

2024 UK Election

The 2024 election saw the largest gap on record between vote share and seat allocation. For instance, Labour won 34% of total votes but secured about 63% of the 650 seats in Parliament, with Reform being in the opposite position, having secured 14% of the vote and only 1% of the seats in Parliament. With 24% of the vote, the Conservatives secured 19% of the seats. The Liberal Democrats received 12% of the vote and 11% of the seats, the most proportionate share in the election, while the Conservatives received 24% of the vote and 19% of the seats.

The key issue here is legitimacy. In a democratic society, laws and government actions must reflect the people's will. However, some question the legitimacy of a party with a near “supermajority” but only receiving ⅓ of the popular vote. In other words, roughly 66% of the UK Did NOT vote for Labour and may disapprove of the laws they enact, yet Labour has a majority that allows it to govern without any real issue.

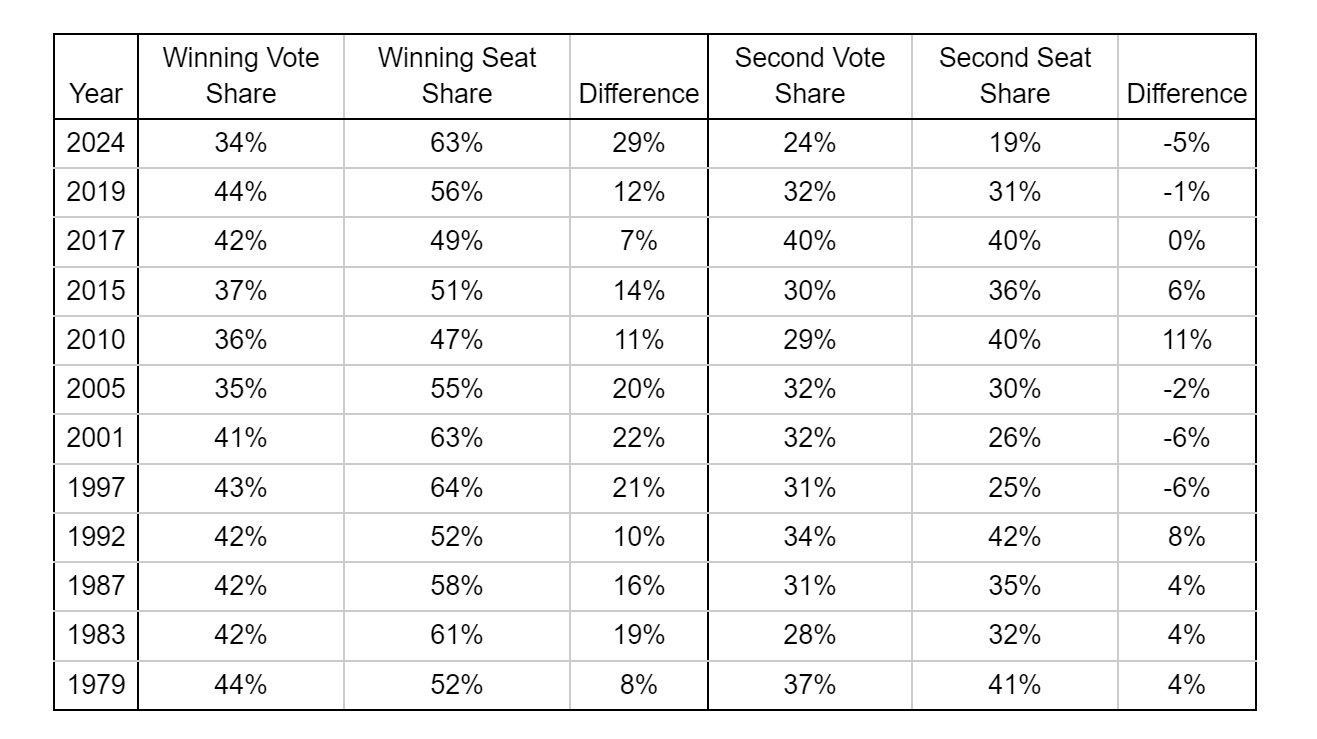

Yet discrepancies like this have happened before, though not as extreme as the 2024 election. The table below lists UK elections going back over 45 years. The difference column highlights the disparity between the number of seats a party has won and their vote share.

Elections in the last 45 years have rarely produced ruling parties with seats distributed proportionally to their vote share. But why is this? The primary culprit is the UK’s electoral system—First Past the Post.

Financial Times montage/Dreamstime

First Past the Post

First Past the Post (FPTP) is an electoral system that elects Members of Parliament (MPs) to the UK House of Commons. The UK is divided into 650 constituencies, each represented by one MP. Voters in each constituency cast a single vote for their preferred candidate, and the candidate with the most votes wins the seat, regardless of whether they achieve a majority. FPTP is used in the UK for general and local council elections in England and Wales. It is also employed in former British colonies like the United States, Canada, and India, while many others have switched to different systems.

FPTP tends to favour a two-party system, as described by Duverger's Law, making it difficult for smaller parties to gain representation. This system often produces disproportionate results, where the number of MPs a party wins does not match their overall share of votes. For instance, in the 2015 UK election, the Scottish National Party won 95% of Scotland's seats with only 50% of the vote. FPTP also creates "safe" constituencies where one party consistently wins and "swings" more competitive seats. This can lead to parties focusing their campaigns on swing seats, potentially neglecting other areas. The system often produces single-party majority governments, even when the winning party receives less than 40% of the total votes.

The simplicity of FPTP makes it easy for voters to understand and for officials to count votes. Each constituency has a dedicated MP who fosters a direct link between voters and their representatives, and the system often leads to stable, decisive single-party majority governments. However, FPTP can lead to unrepresentative outcomes, with many voters feeling their votes don't count, especially in safe seats. This can also result in strategic voting, where voters might vote tactically rather than for their preferred candidate to prevent a less favoured candidate from winning. Additionally, FPTP can exclude smaller parties from gaining representation, even if they have significant overall support.

In the UK context, FPTP has been criticised for producing governments with minority support. For example, governments were formed in the 2005 and 2015 elections with just 35% and 37% of the vote, respectively. In contrast, countries like New Zealand, which switched from FPTP to MMP in 1996, have seen more proportional outcomes and increased representation for smaller parties. These examples highlight how alternative systems can lead to more equitable governance.

Alternative Electoral Systems

Several alternative electoral systems could address the issues seen with FPTP. Proportional Representation (PR) systems, such as Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) and the Single Transferable Vote (STV), offer different approaches to achieving a more equitable distribution of seats based on the popular vote.

Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP): This system combines elements of FPTP with a proportional representation component. Voters cast two votes: one for a candidate in their local constituency and another for a political party. The overall composition of the legislature is adjusted to reflect the proportion of votes each party receives, ensuring a more accurate representation of the electorate’s preferences.

Single Transferable Vote (STV): STV allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference. Seats are allocated based on the proportion of votes each candidate receives, with preferences redistributed until all seats are filled. This method reduces wasted votes and provides a more nuanced reflection of voter intent."

Challenges to Reform

Despite growing support for change, with 45% of respondents favouring PR (versus 26% who want to retain FPTP), there are obstacles. The two major parties, Labour and Conservatives, have historically benefited from the current system, as each has achieved large majorities in different periods that have allowed them to govern without too many issues. On top of that, a 2011 referendum on an alternative voting system was rejected, though many claimed this was not a real attempt at putting PR to a vote among the people.

There are also concerns about the uncertainty created by implementing a new system. Electoral reform would have significant constitutional implications beyond merely affecting election outcomes; it would influence government formation, parliamentary procedures, and the functioning of key institutions. Implementing a new electoral system would likely lead to political disruption as politicians, institutions, and the public adapt to new electoral dynamics. Although proportional representation (PR) systems generally result in more coalition governments, predicting the specific outcomes and impacts is challenging.

To maximise the potential benefits of electoral reform, additional changes are needed in areas such as government formation processes, management of coalition relationships, parliamentary procedures, and devolution and union arrangements. Ensuring widespread public support and legitimacy for a new system could be challenging, necessitating a robust process for selecting the system and potentially a referendum. Introducing a new electoral system would require significant changes to electoral law, voter education, and administrative processes. Additionally, some PR systems are more complex than First-Past-The-Post (FPTP), which could hinder public understanding and acceptance. Balancing competing priorities to design a new system that achieves desired goals, such as proportionality, strong local representation, and governability, while avoiding potential drawbacks can be particularly challenging.

Conclusion

The disparities between the popular vote and seat allocation in the 2024 UK General Election have reignited debates over the effectiveness and fairness of the UK's First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system. Historical data shows that this system often results in disproportionate representation, favouring larger parties and creating barriers for smaller ones. The Labour Party's significant seat majority, despite winning only a third of the votes, underscores the ongoing legitimacy issues and discontent among voters.

While FPTP's simplicity and historical roots have maintained its position, the increasing push for proportional representation (PR) reflects growing public dissatisfaction. Transitioning to a new electoral system would not be straightforward; it would require extensive reforms across various governmental processes and substantial efforts to gain public support and understanding. The complexity and uncertainty associated with such a shift pose significant challenges. Nonetheless, the debate continues as more voices call for a system that better aligns parliamentary representation with the voters' will, emphasising the need to consider both the benefits and drawbacks of potential reforms carefully.